Voilà Viola! Volume 1 ‘Great Brittain’ Grey – Gorb – Britten – Bliss

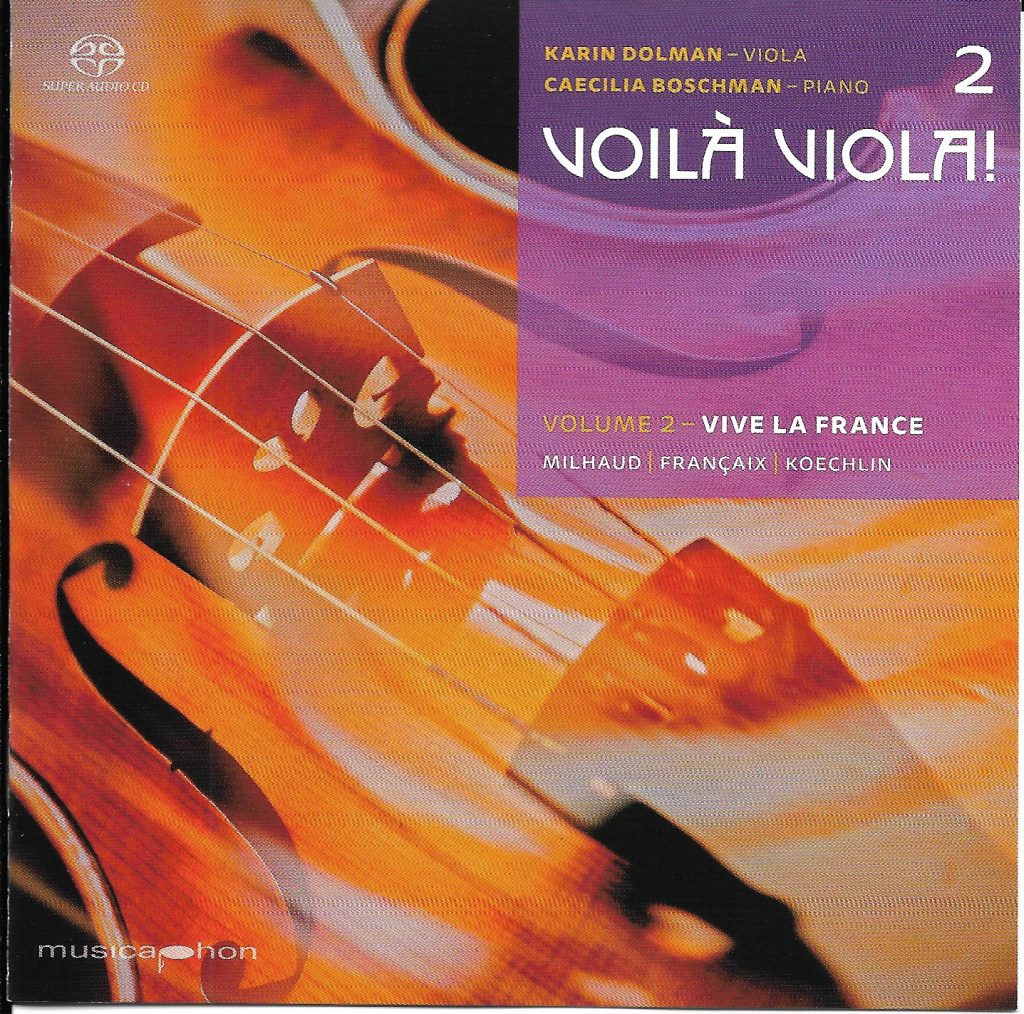

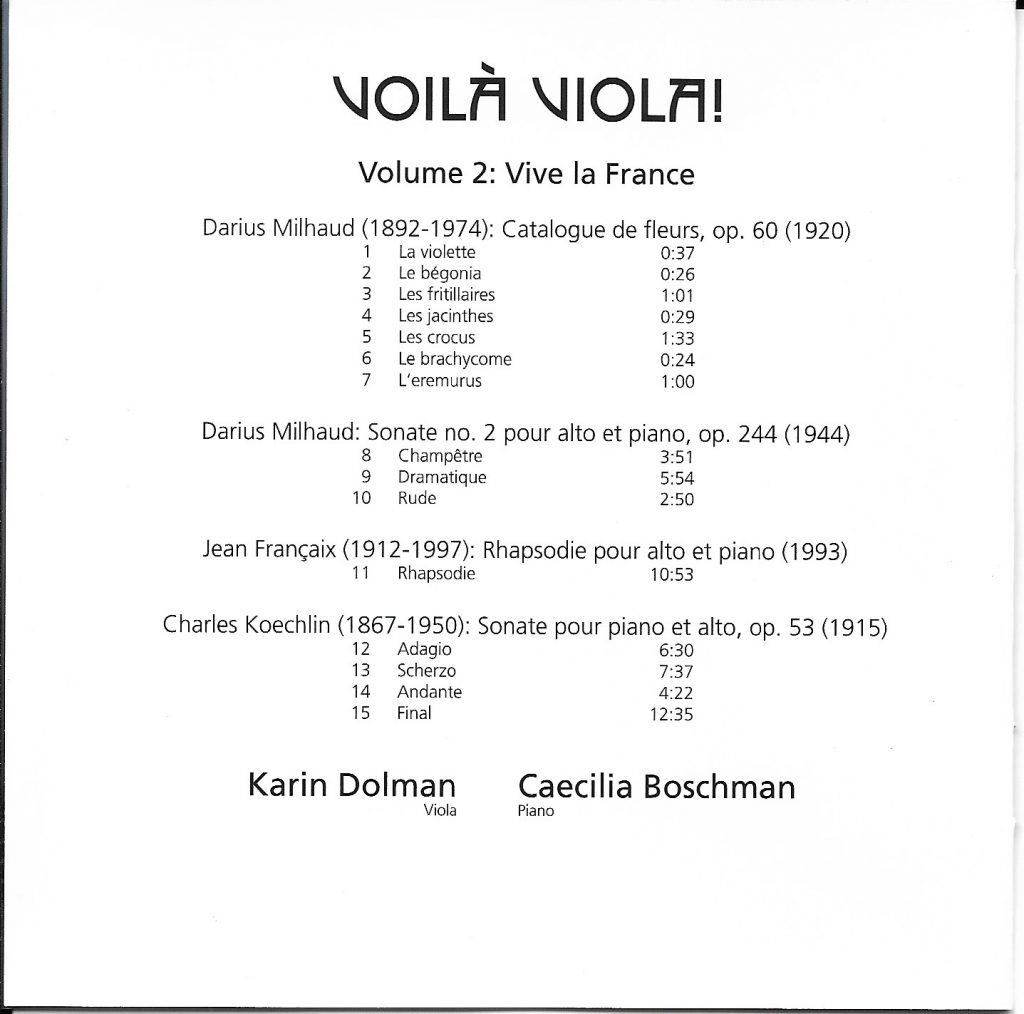

Voilà Viola! Volume 2 ‘Vive la France’ Milhaud – Françaix – Koechlin

Great Britain

The viola seems to be tailor-made for British music. The instrument has a somewhat melancholy character allied to a mildly phlegmatic temperament, and is relatively modest in regard to its sound, certainly in comparison with the violin or the cello. The viola can however also be virtuoso and extremely passionate, and these different aspects are highlighted with a great deal of verve in many a British score for viola. This is demonstrated by the selection of works on this CD.

The development of the viola repertoire in Great Britain in the twentieth century is largely due to just one person, the viola player Lionel Tertis (1876-1975). Arthur Bliss had good reason to write in his memoire As I Remember that it was Tertis who turned the viola, the Cinderella of instruments, into a Princess. To start with, Tertis systematically commissioned composers to write for his instrument, and it is thanks to him that the viola repertoire was enriched with works by Arthur Bliss, William Walton, Arnold Bax, Frank Bridge and Gustav Holst. Following on from Tertis, performers William Primrose (1904-1982) and Cecil Aronowitz (1916-1978) also intensively supported British music, for instance both being involved in the creation of the two versions of Benjamin Britten’s Lachrymae. Primrose moved to the United States in 1937, where he also commissioned a viola concerto from Bartók in 1944.

Geoffrey Grey (*1934) composed his Viola Sonata (1986) for viola player Roger Chase, who was taught by Tertis and who plays on his Montagnana viola. The distinctively full sound of this instrument and the way in which Tertis raised the viola from a modest ‘inner voice’ and the conveyor of rather thoughtful, lyrical music into a brilliant concert instrument, can all be found in Grey’s sonata. The remarkable structure of the piece fits perfectly with the mood swings in Grey’s music: from intensely lyrical to brilliant and virtuoso, from fierce and aggressive to ethereal and enchanting. The entire work consists of a ’theme’ with four variations. The entire first movement (Andante amabile) is the ’theme’, and in various ways each of the following movements shine light on facets from that first movement. The result of this way of working is that, in spite of its frequently contrasting moods, the sonata as a whole has a great sense of unity.

In a sense Lachrymae, opus 48 (1950) by Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) is also bound together by a special variation structure. The full title of this piece is Lachrymae – Reflections on a song by Dowland and, as with the title, the source of the ‘reflections’ is only given in its entirety at the conclusion of the work. This is from a beautiful song by Dowland from the First Booke of Songes or Ayres (1597), and then only the first sentence, ‘If my complaints could passions move’. Although the melody is to be heard first in the bass of the piano part in the Lento of Lachrymae, once all of Britten’s musical thoughts on this song have passed and indeed after another Dowland quote in the sixth ‘reflection’ from another song, namely ‘Flow my teares’ from the Second Booke of Songes and Ayres (1600), only then does ‘If my complaints’ return, endowed with Dowland’s own harmonies. Britten very ingeniously incorporates Dowland’s harmonic language – which is already often strikingly chromatic and expressive for its time – into his variations; seamlessly blending this into the harmonic language of the twentieth century. The original version of Lachrymae was written for William Primrose. However, not long before his death Britten made a second version of Lachrymae or Cecil Aronowitz, for viola and string orchestra.

The two works by Adam Gorb (*1958) on this CD are further examples of the ways in which restrained lyricism, gentle irony and a melancholic undertone can go together in contemporary English music. Gorb is not directly associated with the twentieth-century avant-garde. His greatest successes have come through his virtuoso music for large wind ensembles, the ‘concert bands’ that are so popular in Great Britain and the United States. Gorb’s concert music is expressive, sometimes infused with a jazzy swing and often remarkably down to earth and practical. Both the Humoresque (1986) and the Valse Nocturne (1992) were written for viola player Martin Outram. The Valse nocturne is an arrangement of the slow movement from his Viola Concerto (1992).

The Viola Sonata by Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975) is the masterful conclusion to this CD’s British programme. Bliss composed this three-movement work (Moderato, Andante, Furiant: Molto allegro – Coda: Andante maestoso) for Lionel Tertis in 1933. A year after its completion Bliss gave a lecture and spoke about the viola as “the most romantic of instruments; it is a veritable Byron in the orchestra. The dark, sombre quality – now harsh, now warm – of its lowest string, the passionate rhetoric of its highest string, and its whole rather restless and tragic personality, make it an ideal vehicle for romantic and oratorical expression.”

The partnership with Tetris was so close that Bliss suggested that both his name and that of the viola player should appear on the cover of the score, and indeed all of the qualities of the instrument in general and of Tertis’s playing in particular with his extra-large viola, can be found in this passionately driven sonata. The first two large-scale movements have predominantly restrained tempi, with a lyrical, mild Moderato in sonata form based on two contrasting themes followed by a sombre, brooding Andante. The Furiant therefore works as a brilliant release for all of those previously built-up emotions. It is however characteristic of much of Bliss’s inter-war music that seriousness and melancholy should return in an extended final coda.

Leo Samama, 2016

Vive la France

French chamber music took a while to take international prominence in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. This is not to say that chamber music was not being produced, on the contrary. Well-known and beloved composers such as Cherubini, Reicha, Onslow and Gounod wrote many string quartets (Onslow even writing them in huge quantities…), but chamber music was generally seen as an afterthought. Anyone who wanted to make a career had to compose operas or virtuoso piano works. In addition, brilliant soloists naturally wrote for their own instrument and preferably with orchestra. The nineteenth century, however, did not see many virtuoso viola players. The only violist to make a certain furore in France before 1850 was above all a violinist, and also an Italian: Niccolo Paganini, who had given Hector Berlioz the commission for a viola concerto, resulting in the not so virtuoso but masterly Harold in Italy.

After the fall of Napoleon III and with it the Second Empire, civil culture took precedence over fashionable and grander than grand opera, although opera was never entirely driven out of French cultural life, and audiences at elegant salons with the rich bourgeoisie at home were no less in favour of songs and piano music than before. It was the Société Nationale de Musique, co-founded by César Franck, Camille Saint-Saëns, Jules Massenet, Gabriel Fauré and Henri Duparc and which saw the light of day in 1871, through which attention became focussed on pure chamber music. The slogan of the SNM was ‘ars gallica’ or French art above all, and for a brief period after the end of the Franco-German war this was cause to have strong second thoughts when it came to the influence within the SNM of German chamber music by Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn and Schumann, not to mention the harmonious innovations of Richard Wagner!

Within a few decades leading French composers were enthusiastically writing violin sonatas, cello sonatas, piano trios, quartets and quintets. It seems, however, that the viola was left behind. It was for example found suitable for chamber music with other strings, and sometimes for potpourris based on well-known melodies, but not as a serious solo instrument with piano. This was at least the case in France, as in Central Europe it had gradually gained popularity since Mendelssohn and Schumann. When we look at the list of French viola sonatas written before 1910, it is noticeable that this contains virtually no well-known composer’s names. Furthermore, many a viola sonata from that time was originally composed for cello.

In short, when Charles Koechlin (1867-1950) started sketching a viola sonata in 1902, he had little to fall back on. He had started composing only late in life. Only after training as an officer and a serious illness (TB) did he take his decision to go into music and follow a course at the Paris Conservatoire. From 1890 he wrote mainly songs in a somewhat sumptuous style, related to those of Massenet and Fauré. Sketches for orchestral works or chamber music led to little that met with his approval, until in 1911 he finally considered himself able to take on a series of sonatas. Koechlin had by then come into contact with the Javanese gamelan, studied the new works of his contemporaries Debussy and Ravel and immersed himself in the stories of Rudyard Kipling. At his own calm pace he developed a completely personal and adventurous kind of music, characterised by wonder, curiosity and a strong yearning for unspoiled nature.

The Viola Sonata (opus 53) was an important step in the field of chamber music, and is perhaps his best work from those years. A decade after starting the work he returned to his early sketches and completed the sonata in 1915. The four movements – Adagio (Très lent), Scherzo (Allegro molto animato and agitato), Andante (presque adagio) and Finale (Allegro très modéré mais sourdement agité) – stand witness to Koechlin’s steady but also meticulous development. Indeed, the finale of the sonata is based on early sketches that found their way into the song Sur la grève (opus 28 nr.1). From 1912 he worked continuously on several chamber music works simultaneously, the First String Quartet (Opus 51), the Flute Sonata (Opus 52), the Viola Sonata, the Second String Quartet (Opus 57) and the Oboe Sonata (Opus 58). When he had almost finished the Viola Sonata, he told his professional ally and friend Darius Milhaud that the work was ‘sombre and at the same time intimate’. In that regard it fitted well with the overall mood during the First World War, during which Koechlin and his wife were involved with the Red Cross ambulance service.

Koechlin was however worried that Milhaud, to whom the sonata is dedicated and who as a violist (although he was trained as a violinist) gave the first performance on May 27, 1915, would feel burdened by the sonata’s weighty nature. Milhaud enjoyed the new ‘masterpiece’, but Koechlin remained doubtful. The long melodic lines, the complex rhythm and the dramatic contrasts might well suit a different setting: a piano quintet or a cello sonata, or perhaps even an orchestral work. In 1926 he still played with the idea of orchestrating the sonata… Fortunately, this never happened.

It seems unlikely that Koechlin gave his friend the idea of writing a viola sonata. Milhaud (1892-1974) did not write his first sonata for that instrument until 1944, though he had already written a cantata (Le retour de l’enfant prodigue, opus 42) in 1917 with viola solo, and in 1929 a Viola Concerto (opus 108). The Second Viola Sonata (opus 244) dates from 1944 (the score is marked “Mills 27 June – 2 July”), and as well as the first sonata (opus 240) originated at Mills College (Oakland), where Milhaud began working as a composition teacher after having fled as a Jew in 1940. He held this that post until 1971. The Second Sonata is dedicated to the memory of Alphonse Onnou, the founder of the then famous Pro Arte Quartet, which had also emigrated to the United States.

The layout of this three-part viola sonata (Champêtre, Dramatique and Rude) is typical of Milhaud’s music: the calmly undulating line of Champêtre reveals the comfortable ‘musique d’ameublement’ of this Southern French composer, the stately Dramatique is utterly French, especially in its hidden expressiveness with punctuated rhythms like a twentieth-century Lully, contrasting sharply with the subsequent rough finale. Here as well, although ‘rude’ can be taken to mean ‘rough’, the music is never without dignity.

The seven little flowers of the Catalogue des fleurs (opus 60) date back to the early days of the Groupe des Six, when the members of this illustrious company believed that music should be just as easy to listen to as a nice, lazy chair should be to sit in, hence the idea of ‘musique d’ameublement’. Originally, this opus was a song cycle on texts by Lucien Daudet, who depicted each flower in a pointed text. Successively the violet, the begonia, the fritillary, the hyacinth, the crocus, the Australian daisy and Cleopatra´s Needles. The arrangement of this charming music has been provided by Karin Dolman and Caecilia Boschman.

While Milhaud’s light touch can be traced back to both his Southern origins and the overall aesthetics of the Groupe des Six in the 1920s, and was defended as such even when more modern music styles took prominence after 1945, the airy tone in many works by Jean Françaix (1912-1997) saw them encountering considerable difficulties. Françaix wrote his first important pieces in the mid-thirties, after the ‘roaring twenties’ had been wiped out by a global economic crisis, bringing with it the desire for more serious art. He was also not a southerner, having come from Le Mans in the north. It was only after 1975 that Françaix received greater recognition for his work in his own country and beyond.

On the evidence of the Rhapsodie for viola and piano (1946) we can understand those initial doubts, but not at all that persistent subsequent resistance to such a piece. The playful alternation of movements, sometimes rippling and gently swaying, sometimes pointed and mischievous, with a regular sudden wink to the world of street songs and light chansons, while the harmonic language is sometimes colourful and sometimes contrary, leads to a cheerful chaos, a potpourri of instigations and ideas. Is this ‘exalted’ music? Or is that not the intention? After all, Jean Françaix was averse to any pretension. The original version of the Rhapsodie, namely for viola with wind instruments, percussion and harp, is more disruptive in its sound than the version with piano alone. Those who often listen to Françaix’s music soon recognise the special style, charm and zest for life that speaks from most of his works. Vive la France!

Leo Samama, 2018